On my very first day at school after arriving in Australia, I was taken to the library to meet my classmates. Shortly after being introduced, everyone was encouraged to select a book to read for the remainder of the scheduled reading session. I chose 'Grug has a birthday'. It was the only book with enough words that I recognised. I don't remember the responses from my high school peers. Not on that day. I do remember many other times of awkwardness and embarrassment in the months that followed, as I was called upon to read aloud from the set class text. A fast and proficient reader in my native Dutch language, now at almost 13 years old, I would find myself halted and confronted by words that a five year old native English speaker was able to read, understand and pronounce with ease.

I have always loved reading, learning, and reflecting through writing and forms of creative expressions. Despite my initial struggles adapting to a new culture and language, I loved learning in my new Australian classroom context, particularly English, art and a subject called 'general studies', or what we might think of as 'humanities'. My siblings and I were sent to a small, private Christian school, where the English teacher also taught art. She had a wonderful way of encouraging my vocabulary through art, and this has helped me to see over time that the divisions that we create between disciplines, or knowledge areas, actually suggest a very limiting perspective of learning itself.

To learn means to gain knowledge or skill in a new subject or activity. But it is so much more than that. At its deepest, learning is a process of transformation. The beginning can be a time of difficulty and struggle. It can be very humbling to put ourselves back in a position where we are not good at something. But it is also a time of discovery and a time of wonder. And if we embrace the process of learning, we not only grow in proficiency, capability, skill and knowledge, we become what we are learning. The power of learning is profoundly transformative.

As someone who has always loved learning, I have taken my ability to learn and to have access to quality education somewhat for granted. But historically for many women, and indeed working class populations, this has not always been the case. Several years ago as I was researching for a short lecture series on women in the history of philosophy, I came across the writings of a Dutch polymath and genius, Anna Van Schurman. Today, her main claim to fame is as the first woman to attend a university in the Netherlands, and indeed, one of the first to attend a European university. But her story is so much more than that, for it is the story of a brilliant woman whose genius was recognised by her peers, but who nevertheless had to struggle to claim access to the transformative power of education. In her struggle, she opened the path to many other women.

Anna Van Schurman

Anna Van Schurman (born on the 5th of November, 1607) reflects on her own childhood in her autobiography, Eukleria, written later in life. In this account, it is clear that she considered herself both intelligent and devout from a young age. As well as being able to read by the age of three, Anna recalls that at the age of four years old, she was able to recite from memory the response to the first question of the Heidelberg Catechism, which she later also understood as a deeply spiritual moment.

When Anna was eleven, her father noticed her correcting her older brothers’ Latin grammar, at which point he began to teach her alongside her brothers, encouraging Anna to read classic authors such as Seneca, Homer and Virgil, alongside the Holy Scriptures. In addition, she was taught writing, arithmetic, instrumental and vocal music, various arts – at which she became highly accomplished. At one point, she had made a wax figure of herself, on which she spent ‘at least thirty days’, she writes. This figure was so lifelike that she was asked to pierce one of the beads on the necklace by the Countess of Naussau. At the age of fifteen, Anna impressed the famous Dutch poet, Jacob Cats, with a poem that she composed in his honour.

Anna's father died when she was 19 years old. He’d extracted a promise from Anna to never marry. She readily agreed, and she would later describe marriage as an ‘inextricable, highly depraved bond'. Following her father’s death, Anna, her mother and two aunts moved to Utrecht, which was to be her home for most of her adult life. A year later, she had become known as the ‘tenth muse’, corresponding regularly with male intellectuals. In her late 20s Anna's reputation as Utrecht’s best Latinist led to an invitation to compose a poem in Latin for the University of Utrecht opening. She did so, and as part of her address asked – 'But you might ask what concerns agitate your heart? This sanctuary is not accessible to the great number of women'. Already an advocate for women's education, she now used this opportunity of a public address to highlight what we would today call a gender inequality in access to education. That same year, Anna was personally invited to become the first female student to study at the University.

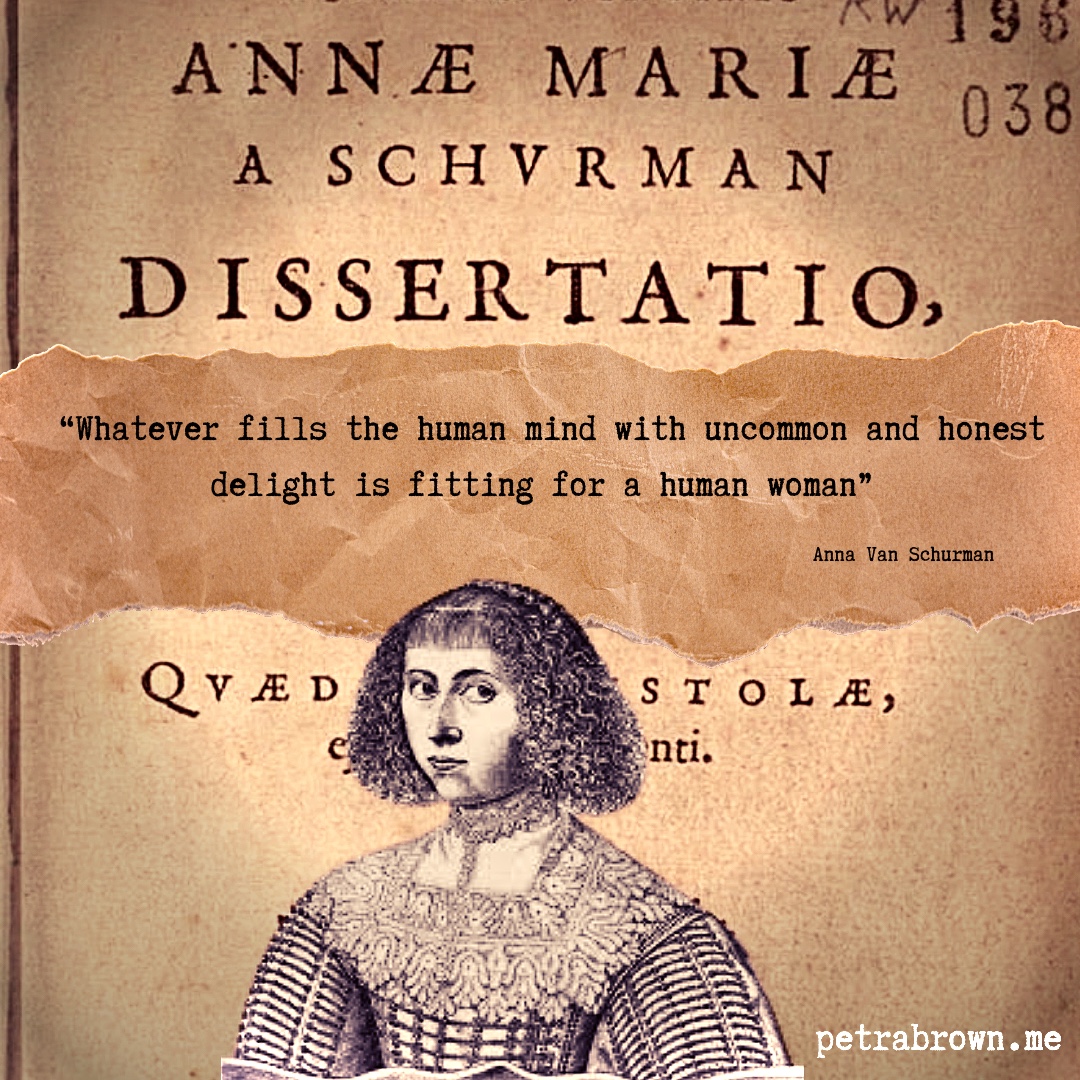

Throughout her adult life, Anna Van Schurman published multiple works on the importance of equal education for women. One of her earlier publications is based on her correspondence with Andre Rivet, theologian and tutor to Prince Wilhelm II. In the Dissertatio, de Ingenii Muliebris ad Doctrinam, et meliores Litteras aptitudine, which was later translated to English as 'The Learned Maid - Or Whether a Maid may be a Scholar’, Anna sets out her arguments using a medieval scholastic technique of formal syllogisms.

The choice of using a scholastic model for her argument is significant, suggests Dutch philosopher Caroline Van Eck. Anna could easily have used the less formal, increasingly prevalent form of humanist literary practice that had begun to replace the medieval scholastic form. The Dissertatio is reminiscent of the style of late medieval scholastic philosophers, such as William of Ockham, who is now famously remembered for the austere simplicity of his arguments (you might be familiar with the term 'Occam’s razor'). Van Eck suggests that the style is a deliberate choice that enables Anna to methodically invalidate the exclusion of women from education. In each syllogism, the women (the minor term) share the universal quality of the universal (the major term): in other words, the particular fits into the whole. It is not a question of changing the universal, but of recognizing that women are already part of it. The formal structure of the syllogism provided the best form to capture this idea. Using the medieval style of rhetoric was also a strategic choice. The quaestio form, composed in Latin, was in line with the highest practice at university at the time, and it forced her male intellectual peers to take Van Schurman seriously. As Van Eck states: ‘By producing a dissertation that satisfied the prevailing academic requirements of rigour and scholarship, she demonstrated that there was at least one woman who was capable of being included in academic debate.'

Anna was initially reluctant to publish this work, but an unauthorized version full of errors already available in Paris forced her hand. The publication of Dissertatio raised her profile even higher. The Dissertatio was one book in a growing market of publications on the question of women and education, and Anna corresponded with various other others on this matter, including the notable proto-feminist French writer, Mari le Jars de Gournay, who had published her own treaty in 1622.

‘An Exceptional Mind’

It is clear that Anna Van Schurman was something of a genius. She had a wide variety of artistic talents, including engravings, sculpture, wax modeling, and the carving of ivory and wood. She also seemed to have a natural talent for languages; she mastered at least twelve languages, including Hebrew, Greek, Arabic, Aramaic, and Syriac. She wrote treatises in Latin and French, composed poems in Dutch, as well as compiling a grammar of an extinct ‘Ethiopic language’ of interest to Biblical exegetes.

Anna was described by her admirers as a miraculum or monstrum naturae, a ‘marvel of nature’. Indeed, as Anna’s earliest biographer, Pierre Yvon (1751) enthused: 'To have been in Utrecht without having seen Mademoiselle de Schurman was like having been to Paris without having seen the king' (cited in Pal 2012). Her influence extended well beyond her own immediate Dutch-speaking community.

Yet, to be a woman with an 'exceptional mind' proved to be a double-edged sword. Throughout her correspondence with the theologian Andre Rivet, Anna had been trying to work out whether a life devoted to study was to be her path. Andre had encouraged her. The life of learning, according to Rivet, was acceptable for exceptional women who, thanks to the extraordinary grace of Heaven, excelled above other women. Yet it was this idea that she was somehow ‘exceptional’ that disturbed Anna. She did not think herself particularly exceptional or a monstrous natura, a miracle of nature. She asked instead - Shouldn’t all Christian women devote themselves to studying, particularly if learning reinforces the path to salvation, a path available to all?

A Maid Wishing To Be A Scholar

In her writings, Anna van Schurman describes the characteristics of, and conditions for, a 'maid' wishing to be a scholar. She should be ‘endued at least with an indifferent good wit, and not unapt for learning’, she must have some basic necessities so that she can be free from ‘want’ (dependence on others), she must be excepted from ‘Domestick troubles’, and to this end she should remain celibate as she matures and employ a housekeeper. Finally, she should be motivated by the love of God, and the salvation of her own soul, as well as show a willingness to instruct her family and other women, should the opportunity arise.

As to what she should study, this should be guided by the capacity and condition of the Maid herself. Anna includes Rhetoric, which was discouraged for women as a discipline, lest they might then wish to enter the public sphere. She further believed women should be able to study Law, Military Discipline, Oratory in the Church, Court and University. Although such studies can be considered ‘less proper and less necessary’ (given that they are concerned with earthly, not heavenly ideas), a woman should not be excluded from such subjects, not even from ‘understanding the most noble Doctrine of the Politiks or Civil Government', writes Anna later, in Eukleria. Indeed, says Anna, 'Whatever fills the human mind with uncommon and honest delight is fitting for a human woman.'

For Anna, education should be available to all women, including those of modest intelligence, and women should be able to study whatever they wish. After reading the Disseratio, Andre Rivet expressed that it ‘caused him concern for some little while’. Rivet and his contemporaries tended to see women like Anna as exceptions. Rivet assumed that there were exceptional women. He could accommodate these exceptional women, but ‘ordinary' or less gifted women has an assigned place (as per tradition and convention) that did not include education. Rivet’s position was that, in general, women were not capable, although there were exceptions. Van Schurman argued on the basis of theology, natural law and ethics that women had both been endowed with reason (equal to men) and had a duty to educate themselves to ensure virtue and the path of salvation. Van Schurman's position was that women were capable, although there were also exceptions of genius (as with men).

There is a lot more to the story of Anna Van Schurman, whose intellectual and creative gifts found some recognition in her own time and place. But her position as an 'exception' to her peers also led to loneliness, isolation and frustration. Her later life took yet more twists and turns, which I will need to address in a follow up post! Today, I want to acknowledge that without women like Anna Van Schurman, I would not have the privilege of being able to take my education for granted. My access to education was paved by a Dutch polymath, who despite her genius, was required to sit behind a screen whilst attending University lectures, lest she should distract her male colleagues from their studies. Anna was able to take part in higher academic learning, but she would never attain a degree. It would be another 200 years before a female student could 'graduate' from a Dutch university. As I write this post, we are about to celebrate International Women's Day as a global community. The United Nations reports that across the globe today, girls and boys participate equally in primary education in most regions, and girls tend to do better than boys in terms of academic achievement. In tertiary education, women outnumber men, and enrolment is increasing faster for women than for men. Yet, within the STEM disciplines, women continue to be underrepresented, representing only slightly more than 35% of the world’s STEM graduates. Women are also a minority in scientific research and development, making up less than a third of the world’s researchers. It is a sober reminder that there is more work to be done to include women in the hallowed corridors of knowledge production.

Further reading

Interested in learning more about the life of Anna Van Schurman? I am indebted to the sources below for my own reading and growing knowledge.

Project Vox - curates and highlights the intellectual contributions of early modern women in history of philosophy, and has an extensive and detailed entry on Anna Van Schurman.

Barbara Bulckhart's chapter 'Self-Tutition and the Intellectual Achievement of Early Modern Women: Anna Maria van Schurman (1607-1678)' in Women, Education, and Agency, 1600–2000 (2010).

Carol Pal's book, Republic of Women : Rethinking the Republic of Letters in the Seventeenth Century (Cambridge 2012) has a chapter 'Anna Maria van Schurman: the birth of an intellectual network'.

Pieta Van Beek's PhD on Van Schurman, and further research and writing on Anna Van Schurman

Caroline Van Eck's chapter 'The First Dutch Feminist Tract'?' in to Choosing the Better Part - Anna Maria van Schurman (1607–1678) (1996)

Selections of Anna Van Schurman's own writing: avaialble in Whether a Christian Woman Should Be Educated and Other Writings from Her Intellectual Circle (1998)